Just when they'd finally shaken off Catholic guilt and parent guilt, people of a certain age are now being saddled with boomer guilt and it's getting heavy.

Intergenerational sniping is nothing new, but Australia's cut-throat housing market has taken it up a few notches. Post pandemic, boomers have come under increasing flak for their disproportionate share of property wealth while Gen Ys and Millennials are being flayed by skyrocketing rents and property prices, effectively cruelling their chances of putting together a deposit, let alone buying a home.

'Boomer guilt' is a term loosely bandied for people from the older generation feeling some niggling discomfort around the economic positions they forged in the long period of post-war prosperity compared to the environment their kids and grandkids are facing. (Of course, some don't feel it at all - 17% interest rates, anyone? Perhaps some smashed avo?)

The stats say it all. Baby boomers (demographically defined as being born between 1946 and 1964) make up around a quarter of the population but own more than half Australia's national wealth. Boomers have the highest home ownership rate of all cohorts (above 80%), with much of their wealth tied up in the property market. Some estimates put it at around two trillion dollars' worth.

Did boomers break the property market?

Blaming boomers for the plight of the housing sector is to ignore the role of successive government policies over many decades and the perfect storm of variables that have led to the current crisis. It also overlooks the fact not all boomers are cashed-up property owners and can also be victims of housing stress and insecurity.

However, a number of studies have concluded boomers indeed had an easier path to home ownership. The Centre for Independent Studies chief economist Peter Tulip (pictured below) ran the numbers and concluded current homeowners are paying a bigger share of their income in interest than homeowners in the 1980s, despite much lower interest rates now.

This is because current homeowners are carrying much larger debts relative to their income and assets.

"Although interest rates were significantly higher in the 1980s, home prices relative to income are roughly twice what they were a generation ago while access to finance is harder," Dr Tulip told Savings.com.au.

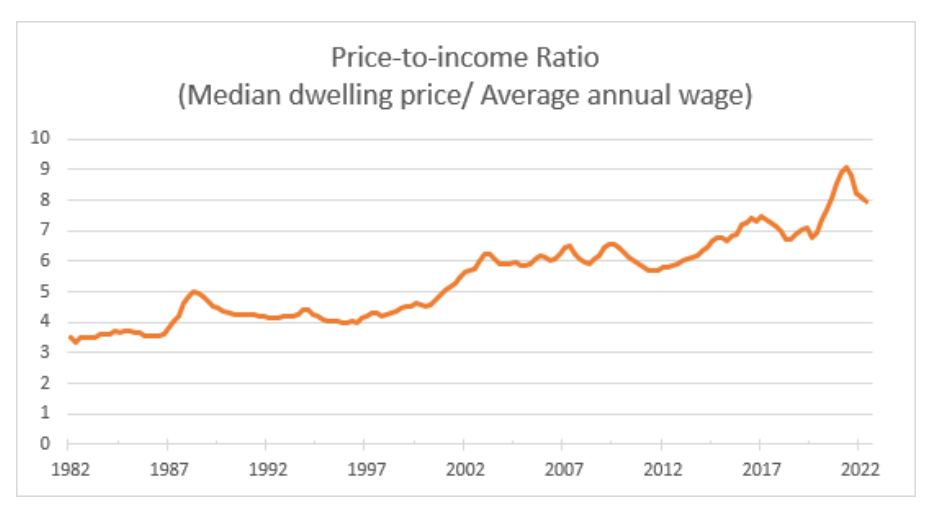

The chart below tracks the median dwelling price in Australia to the average annual wage (price to income ratio) over the 40 years to January 2023.

In 1989, when mortgage rates peaked at 17%, the median house price was five times the average annual wage. During the post-pandemic housing boom in 2022, it was nine times. In January 2023, it was 7.9 times.

Source: Centre for Independent Studies

Dr Tulip said for first homebuyers, although interest rates are more manageable now, putting together a deposit to enter the housing market is much harder, particularly with rents at record highs.

"Home ownership is increasingly difficult," he said.

Investment bank Jarden Australia estimates the number of first homebuyers receiving parental support has increased five-fold in the past five years with around 60% of first home buyers now purchasing a home with some form of parental contribution.

Enter the Bank of Mum and Dad

Perhaps there is some element of boomer guilt underlying the stunning rise of the Bank of Mum and Dad, now ranked somewhere between the fifth and ninth largest home lender in Australia, according to the Productivity Commission.

A Commission research paper entitled 'Wealth transfers and their economic effects' found the number of children receiving home loan assistance in the form of 'gifts' from parents has doubled in the past 20 years. Last year, the figure was put at $2.7 billion for the sole purpose of helping young people achieve property ownership.

Recently, the king of cashed-up baby boomers David Koch (pictured below) issued a warning to "guilt-tripped parents" not be too soft with their gifting policies. In an article entitled 'Beware the risks of the Bank of Mum & Dad', Koch urged parents playing the role of a bank to start acting like one, including lending rather than gifting cash.

"Treat the loan as a business transaction," Koch advised, "and draw up a formal agreement between each party outlining the terms of the deal, including a set repayment schedule.

"Using a lawyer to draft this help to avoid potential pitfalls, signals that you're serious and can also help to ensure the money stays in the family if the child's relationship ends."

Koch noted he'd seen too many of his friends lose "big chunks" of their savings and have to scale back their retirement lifestyles when they act as a family bank and things go wrong.

The pitfalls of boomer guilt

Koch is not alone in his observations. Two sociologists recently published a study into parents gifting children money for home ownership. Julia Cook, from the University of Newcastle, and Peta Cook, from the University of Tasmania, interviewed 52 adults, both parents and children, who had recently given or received financial assistance for purchasing a home.

The amounts transferred ranged between $5,000 and $500,000. The average was around $75,000 although some amounts were much higher. (Jarden's research puts the average at around $70,000 nationally with contributions varying widely according to state and territory property prices.)

The common themes that emerged from the study were the lack of clarity, on both sides, as to whether the payments were gifts or loans. In some cases, what some parents perceived as a loan was construed as a gift by their children. Nearly all transactions were entered into without documentation or legal advice.

The closest any older person came to formalising the arrangement was if they were asked to provide a so-called 'gift letter' to their child's lending institution. Gift letters are formal, legal documents stating the parent's contribution is a gift and not a loan. This is because a loan would be counted as a debt by a child's lender and effectively reduce the amount they would be able to borrow, making it harder for them to get a mortgage.

The study noted some parents may feel obligated to provide gift letters even when they and their adult children were regarding the contribution as a loan. Very few of the parents in the study sought legal or financial advice.

What the experts say

The internet is awash with Australian law firms warning about the many risks to parents providing cash or loan guarantees for their children to enter the property market. Although there are no official figures, some mortgage industry estimates put the incidence of home loan defaults at three to five times more likely for first homeowners who've taken on loans with parental support than those who obtain the loans on their own financial merits.

Co-principal of DBL Solicitors John Devlin (pictured below) said he's seeing a rising incidence of parents helping kids with financial assistance before they approach lenders. He urges people to seek legal and financial advice before they commit to anything.

"It's a very big thing with a great deal of risk associated with it," Mr Devlin told Savings.com.au. "Banks are in the business of lending money and have in place sophisticated systems which allow them to assess the risk involved in lending someone money.

"If after applying those systems, a bank refuses to take the risk, why should mum and dad step in and take that risk?"

He said parents needed to ensure they're able to maintain their asset base to pay for their own retirement and wellbeing and calculate whether they can afford to lose the money if disaster strikes. There are many variables to consider: their child losing their job, separating or divorcing, or the property falling in value.

Guarantors and gifters beware

Mr Devlin has seen worst-case scenarios play out when parents act as guarantors to their children's loans.

"A guarantee is a promise to pay if another person does not," he said. "It is a very big thing. It is not just a nice gesture.

"I have seen parents lose their own homes and savings and fall in bankruptcy as a result of children defaulting on a loan they have guaranteed."

Mr Devlin said at least parents acting as guarantors for their children's bank loans are generally forced to seek legal advice as part of the loan conditions. When they gift money to their children to make it appear the child has saved the money themselves, they can set up their children - and themselves - for dire consequences.

"I think the banks at the moment are pretty good at looking at credit applications and smelling a rat if someone earning very little at a young age has supposedly saved a huge amount of cash," Mr Devlin said.

"The bank will generally question the applicant and if they suspect the applicant is being dishonest, I would hope the bank would refuse the application."

See: What are genuine savings?

In other cases, lenders may ask a loan applicant and their parents to co-sign a declaration confirming the parental contribution is a gift with no expectation of repayment. Mr Devlin warns people against doing this if there is an undocumented agreement or understanding the money will be repaid at a later time.

"If you sign a declaration your money was a gift and it comes to light [it wasn't] during some kind of disaster, then you have signed a false declaration.

"That is bad - it is a crime, and it will stay with you for life if you are convicted. Any future loan applications, insurance applications, or jobs that rely on honesty or being a fit and proper person are gone once you tell that lie."

Assuaging boomer guilt: other ways to help young people buy a home

Providing the cash for a home deposit or becoming a guarantor on a home loan is all very well if you can comfortably afford it and are financially prepared for the worst to happen. But for boomers who aren't in the financial position or are uncomfortable with the risks, there are other ways to provide practical assistance to help your children - or other young people - get a foothold in the property market.

Co-ownership

Rather than gifting or lending money, parents can consider becoming a co-owner of a property with their child, in legal terms 'tenants in common'. As an example, if a child needs a 20% deposit to buy a house but is in a position to borrow the rest, the parent could take a 20% interest in the home with the child purchasing the other 80% and servicing the loan themselves.

This effectively makes the financial contribution part of a legal contract. It also means a parent is receiving something tangible in return for their support. Along with the deal, a co-ownership agreement should spell out how expenses and/or income of the property will be shared and what happens if one party wants to sell.

The parent will also need to make provisions in their will for what happens to their share of the property after their death, particularly if there are other siblings. These considerations can be discussed and formalised through seeking financial and legal advice.

See: First Home Buyer Loans and Grants

If you're looking to buy a home or looking to refinance, the table below features home loans with some of the lowest interest rates on the market for owner occupiers.

| Lender | Home Loan | Interest Rate | Comparison Rate* | Monthly Repayment | Repayment type | Rate Type | Offset | Redraw | Ongoing Fees | Upfront Fees | Max LVR | Lump Sum Repayment | Extra Repayments | Split Loan Option | Tags | Features | Link | Compare | Promoted Product | Disclosure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

5.54% p.a. | 5.58% p.a. | $2,852 | Principal & Interest | Variable | $0 | $530 | 90% |

| Promoted | Disclosure | ||||||||||

5.49% p.a. | 5.40% p.a. | $2,836 | Principal & Interest | Variable | $0 | $0 | 80% |

| Promoted | Disclosure | ||||||||||

5.64% p.a. | 5.89% p.a. | $2,883 | Principal & Interest | Variable | $250 | $250 | 60% |

| Promoted | Disclosure | ||||||||||

5.64% p.a. | 5.89% p.a. | $2,883 | Principal & Interest | Variable | $248 | $350 | 60% |

|

Rent deal

Another way to help your child - or any young person - to get a home loan deposit together is to allow them to rent your investment property for 'fair' rent. The Australian Taxation Office allows landlords to set their own rental amount but warns if the rent is substantially below market rates, there may be tax implications as to what can be claimed in deductions. It's worth checking with an accountant on a workable rent that will satisfy income, tax, and altruistic requirements.

If you're renting your property to a child or family member, industry experts agree it is wise to sign a formal rental agreement so it's clear what the expectations are on both sides. It can also set the renter in good stead for making regular weekly/fortnightly/monthly rent payments just as they would be expected to when they eventually service their own home loans.

Let the kids move back in

If you live in a large home and are up for it, you can invite your child or children to move back in rent-free to allow them to get in a better position to save for a deposit and eventually qualify for a home loan on their own merits.

Multigenerational living is standard in many parts of the world but might take some getting used to if your kids are returning to the nest after living out of home for some time, particularly if they've got a partner or their own children in tow. (Good luck with that.) The breathing space from paying rent can also give prospective first homebuyers the opportunity to investigate whether rentvesting or nestvesting might better help them achieve their homeownership aspirations.

Downsizing

Another way to foster intergenerational cohesion is for boomers to sell their large family home and move into something more suited to their current needs, often referred to nowadays as 'rightsizing'. There have been a number of government incentives over the years to encourage older Australians to do just this, including superannuation benefits for lump sum contributions after the sale of a family home and stamp duty concessions.

See: Should you downsize? The Pros & Cons

This frees up family-friendly homes for younger purchasers. Some parents might even investigate options for their own child or children to purchase the house, or equity in the house, if they are in a position to. If it's a principal place of residence, there won't be any capital gains tax on the transaction. However, if the sale price is considerably less than the market value of the property, the ATO can apply the 'market value substitution rule', deeming the seller has received the market value at the time of the transfer. Again, consult your accountant and lawyer.

Pay off the kids' HECS debt

Rather than giving your kids cash for a home deposit, consider paying any remaining HECS/HELP debts instead. In theory, they are still able to get a home loan with an existing student loan but having a HECS debt can affect how much a home loan applicant can borrow. In simple terms, a HECS debt can impact debt-to-income ratio, calculated by dividing their debts and liabilities by gross income. Many lenders use this ratio to determine an applicant's ability to make home loan repayments.

Paying out the kids' HECS debts can also assuage boomer guilt in those who might have received a free university education between 1974 and 1989. As with most financial gifting, it's wise to seek professional financial advice first to be clear on any repercussions according to individual circumstances.

Investing in affordable housing initiatives

If, after helping your own children, you are still drowning in boomer guilt, you can consider investing in affordable housing initiatives. There are various government, private, and not-for-profit schemes for investors to contribute to affordable and community housing projects around the country.

The federal government provides a number of incentives for investors in such schemes such as rate and tax rebates, planning concessions, and land contributions. The ATO provides tax advice on investing in affordable rental housing. Some state governments also provide additional contributions to investors.

Vote one

Baby boomers (and older) are no longer the largest voting bloc by numbers in the Australian electorate. They were outstripped by Gen X and Gen Y combined at the 2010 election when both blocs made up roughly half the voting demographics. By the 2022 election, the proportion of boomer voters had fallen to less than a third of the electorate.

Yet the residual economic wealth of boomers has seen them continue to hold political clout. People aged 65 and over are the drivers of real household consumption in Australia. The run of interest rate increases designed to stamp out consumer-driven inflation has failed to touch many boomers who overwhelmingly are not paying mortgages on their homes. If all this doesn't seem entirely fair, you could reframe your voting intentions or actively lobby governments at all levels to make real changes to housing policies.

Savings.com.au's two cents

Baby boomers shouldn't shoulder the whole blame for the current state of the housing market. People can't help the times they were born into and the opportunities it may have afforded them, including more affordable housing compared to income, easier credit, better job security, negative gearing, free education (I should probably stop now). More and more boomers are wanting to help their children achieve the home ownership aspirations they had in a different era. This is an admirable gesture but needs to be carefully thought through.

It may well all work out wonderfully and parents can feel satisfied they were able to help their kids in such a practical and timely way to set them up for the future. But finances and families can be a volatile mix, particularly if things don't go to plan or parents have more than one child wanting or expecting their help. Seek both financial and legal advice and make clear what the expectations are on both sides before committing to anything. Always make provisions for worst-case scenarios to play out and be sure you can cope with them if they do.

If you're not in a financial position to offer cash or sign up as a guarantor to a home loan, there are other ways you can try to do your bit - and that should be fine as well. Maybe the intergenerational playing field is not level but it's probably not all your fault, nor your sole responsibility to try to make amends. As they say, the past is a foreign country. No doubt the future will be too.

Main image by Matt Seymour on Unsplash

In text images supplied by Centre for Independent Studies, Channel Seven, DBL Solicitors

Ready, Set, Buy!

Learn everything you need to know about buying property – from choosing the right property and home loan, to the purchasing process, tips to save money and more!

With bonus Q&A sheet and Crossword!