There's a lot of jargon out there, used by financial types who love to make things sound more complex than they are. You probably don't need to bother learning all of the jargon, but it helps, even if it sounds like you’re speaking Klingon.

It might not seem important, and in regular life, it probably isn’t. But just know there's strings being pulled in high finance that can affect what's going on at the consumer level, such as what you pay on your mortgage..

What is an RMBS? A crash course

Residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) - or mortgage bonds - are essentially pools of home loans that investors put their money into for a steady return, either at a maturity date or at certain intervals.

There are other types of securities, such as asset-backed securities (ABS), that pool automobile and other machinery loans together, but for the sake of simplicity we’ll focus on residential mortgage-backed securities - ‘mortgage bonds’ for short.

The bonds have certain pools of home loans sorted by credit-worthiness and investors can put their money into these levels - called tranches. The injection of money gives the home loan originators more cash to play with, and to potentially offer lower interest rates for the borrower.

How do I know if a mortgage bond is safe?

If you were around for the global financial crisis (GFC), or even if you’ve just watched The Big Short, you might think mortgage bonds are pretty risky assets.

There’s always going to be some sort of risk involved - it is after all an investment product - but mortgage bonds are historically safer than other types of investments, but know that past performance is not an indicator of future performance.

Fun Fact: In Australia, no prime RMBS has ever caused an investor to lose money through default.

To assess mortgage bonds' relative safety, they are rated by the top credit agencies such as Fitch, Moody's, and Standard and Poor's (S&P) into categories such as AAA, AA+, AA, AA-, and so on (slight variations may occur between agencies).

AAA is described as 'almost no risk of default' - anything below BBB- is rated 'non investment grade' or highly risky.

The higher the rating, the earlier your interest is paid but the lower your rate of return - for assuming more risk you get a higher interest rate, but you are paid last. Depending on the particulars of an RMBS issuance, if you invest in the BBB tranche, for example, and the AAA tranche starts defaulting, you’ve almost got no chance of being paid interest. That’s how RMBS are potentially risky.

For reference, below is a table from S&P and Moody’s on default rates up until 2008 of US corporate bonds i.e. how often the underlying investments - home loan borrowers - fail (in percentage terms).

You can see that there is a sharp uptick in default rates once you slip below investment grade.

|

Ratings |

Moody’s - default rates |

S&P - default rates |

|---|---|---|

|

Aaa/AAA |

0.52 |

0.60 |

|

Aa/AA |

0.52 |

1.50 |

|

A/A |

1.29 |

2.91 |

|

Baa/BBB |

4.64 |

10.29 |

|

Ba/BB |

19.12 |

29.93 |

|

B/B |

43.34 |

53.72 |

|

Caa-C/CCC-C |

69.18 |

69.19 |

|

Investment Grade Overall (i.e. BBB<) |

2.09 |

4.14 |

|

Non-Invest Grade |

31.37 |

42.35 |

|

All |

9.70 |

12.98 |

Source: US Government Publishing Office, 110th Congress

How does the everyday person invest in mortgage bonds?

Here’s the thing - you can’t. Well, at least not directly. You can’t just go to Commonwealth Bank, for example, and say, “I’d like to invest in your A2 tranche of your ‘Generic Bond Name’ issuance please”.

You either need serious cash i.e. in the tens of millions to invest through a hedge fund, or you need to be an institution. There are very few straight-to-source options for the everyday punter, however there are a few indirect avenues:

-

Firstmac High Livez: High Livez is a managed fund that invests in prime RMBS from institutions such as Westpac, CommBank, BOQ and more. Investors can start with as little as $10,000.

- Blossom Micro-Investing: Blossom targets 'safe' investments like corporate and government bonds, as well as RMBS, with a targeted 3% p.a. return.

- Latrobe Financial: The institution offers a range of retail-level investment products, backed by pools of mortgages and other 'Australian dollar assets'. Terms range from just two days to five years, with a variety of risk profiles. Minimum investment is $10 with three of five profiles.

-

Through your super: Depending on your super fund, of course, you may be investing in bonds. However, this is more likely to be bonds issued by the Treasury i.e. Government bonds.

-

Through investment funds: Investment funds like ETFs (exchange-traded funds) and LICs (listed investment companies) may contain RMBS in their portfolios, particularly ones with a big portion of fixed income assets. While there are many RMBS-focused ETFs in the US, there are very few, if any, in Australia. However there is at least one RMBS-focused LIC listed on the ASX, namely the Gryphon Capital Investment Trust (CGI).

We aren’t endorsing any one area of investment, and you should know that every investment comes with some form of risk. In the interests of full disclosure, Savings.com.au is part of the Firstmac Group.

Securitisation and the Global Financial Crisis

RMBS and other securities may carry a bit of a bad smell, a hangover from the global financial crisis, when they were one of the catalysts for big bank collapses in the US.

Investment banks such as Lehman Brothers, and Bear Stearns, were all heavily leveraged (had a lot of exposure) in the area.

The problem there was the credit ratings agencies were not doing their due diligence, and rated subprime pools of mortgages as investment-grade.

This was due to pressure by investment banks, which paid big money for credit agencies to rate their bonds favourably.

The situation was made worse by investment banks deliberately pooling subprime loans into investment products, and calling them CDOs, or collateralised debt obligations.

CDOs were generally far riskier, yet somehow achieved higher ratings than they were worth.

-

The situation was made even worse, when the investment banks - which quickly learned of the failing mortgage market - hedged their bets with insurance companies by buying ‘credit default swaps’ or CDS. A CDS essentially puts the burden of the debt on the insurer, who in turn receives a premium.

-

A lot of insurance companies such as AIG thought they were swapping safe mortgage bonds, not junk bonds, so they saw the premiums as ‘free’ money. However, they soon assumed a lot of debt as the bonds started defaulting, which ultimately caused AIG to fail.

At the ground level, lenders' relatively loose and predatory lending criteria at the time also had a huge part to play.

-

For example, in the US it was common to sell fixed-rate mortgages to low-income borrowers that transitioned to adjustable-rate mortgages with sky-high interest rates two years later, called teaser rates.

-

Worse still, some products had ‘payment holiday’ periods at the start of the loan, say for two years, where a consumer didn’t have to pay anything but the interest rate was still accruing, essentially ‘kicking the can down the road’.

All of this may have gone unnoticed if homes continued to go up in value, but the glut of houses being built in the US between 2001 and 2006 - and the amount of risky borrowers lured into the market by teaser rates - made the situation a brewing storm.

When homes lost value, and subprime borrowers defaulted on their mortgages and walked away from their homes thanks to non-recourse lending, the AAA securities investors thought they were piling into, were revealed to be BBB- or worse as the default rates climbed.

The mortgage bond market ended up imploding, causing investors to lose money and withdraw from the market.

What about mortgage bonds recently?

In July 2021, Macquarie completed a monster $3.8 billion RMBS deal, the largest since Commonwealth Bank's $4 billion arrangement in 2014.

For mainstream banks and lenders, RMBS fell a bit by the wayside through 2020 and the first half of 2021, largely due to the introduction of the Reserve Bank's Term Funding Facility.

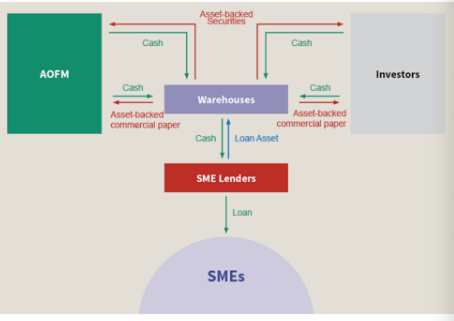

Further back, in March 2020, the Federal Government, through its debt management arm the Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM), announced a $15 billion package to support smaller lenders and non-banks by investing in their mortgage bonds.

This was designed to generate cash for these lenders at a time when not many banks are trading with one another, due to the credit crunch caused by coronavirus. Westpac reported that in Q1 2020, only around $6.5 billion was placed in the public Australian securitisation market - a small amount considering that over the whole of 2019, more than $45 billion was issued. This credit freeze is why the AOFM is ramping up investments.

Generally, the AOFM is targeting relatively safe mortgage bonds, like it did in the past. However, this time it announced it will have a ‘warehouse facility’ arrangement, investing in other types of debt such as assets (cars, machinery etc), and small business lending. This basically opens the investments up to other types of securities with other ratings.

The Government previously had a similar arrangement in 2008 when the world was in the grips of the Global Financial Crisis. However, in those transactions, the Government only invested in AAA mortgage bonds. This was also a $15 billion deal, and was wound-down in 2013.

An illustration of what the Government is doing in 2020 is below (confusing, right?)

Jargon and acronyms explained

Bust these out at the family barbecue and you’ll be much cooler than your cousins talking about lame cryptocurrencies, which are so 2017*.

- AOFM - Australian Office of Financial Management: Part of the Federal Treasury, and manages the Government’s debt portfolio.

- BBSW - Bank Bill Swap Rate: The interest rate at which banks decide to lend to each other, managed by the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX).

- CDO - Collateralised Debt Obligation: Pools of subprime mortgage bonds and their tranches re-packaged as investment products.

- CDS - Credit Default Swap: An insurance policy used to hedge risk on mortgage bonds. A derivative investment product offered by the big insurance corporations.

- Non-Conforming: Tranches and bonds that carry lower-rated mortgage pools in them.

- Prime: Mortgage bonds that carry credit ratings of BBB- or better. Subprime is anything below that.

- RMBS: Residential Mortgage Backed Securities i.e. mortgage bonds.

- Tranche: A ‘slice’ of a mortgage bond that investors can buy into e.g. the BBB tranche of a mortgage bond.

*You may be told to shut up by Uncle Herb and barred from any future gatherings.

Article first published 30 April 2020, last updated 1 October 2021

Photo by La-Rel Easter on Unsplash

Ready, Set, Buy!

Learn everything you need to know about buying property – from choosing the right property and home loan, to the purchasing process, tips to save money and more!

With bonus Q&A sheet and Crossword!

.jpg)

Harry O'Sullivan

Harry O'Sullivan

Bea Garcia

Bea Garcia

Denise Raward

Denise Raward

Harrison Astbury

Harrison Astbury