Since slashing the cash rate to its record-low of 0.10% in November 2020, Australia’s central bank has left it untouched for nearly 16 months.

With bated breath, many economists expect a cash rate hike as early as next week - or in June - with many more increases likely to roll in afterwards.

A big chunk of homeowners have never experienced a cash rate hike before and may not know what to expect this time around.

Let’s take a trip down memory lane and look at what happened the last time the RBA hiked the cash rate. Can we learn from the past and look to the future with comfort, or should we brace for the tough times ahead?

A look at history: What happened last time the cash rate increased?

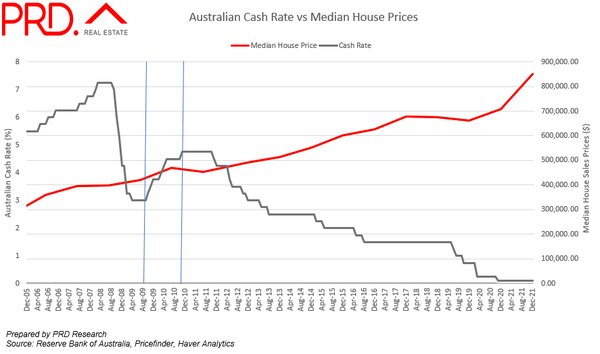

The last time the RBA increased the cash rate was in November 2010, but the cash rate rose multiple times over about one year from October 2009 and November 2010. This was in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

In the space of just over 12 months, the cash rate rose from 3.25% to 4.75%, which represents an increase of 175 basis points. The 4.75% cash rate held steady for 12 months, and then the first cut came in November 2011 to 4.50%.

Shane Oliver, Chief Economist at AMP, said the standard variable mortgage rate went from 5.78% in September 2009 to 7.79% in November 2010.

Pictured: Shane Oliver, Chief Economist at AMP

“On one hand, you can argue that the basic message is that higher interest rates cause falls in property prices, and that same logic will apply here,” Dr Oliver told Savings.com.au.

“[This is] simply because as interest rates go up, people are unable to borrow as much, and therefore, they're unable to pay as much for their houses.

“The other thing that happens when interest rates go up is that some people default on their loans, and that causes forced selling. So there’s less demand and increased supply.”

Dr Oliver said there are a few things that make this cash rate hike different from the last one.

“What makes this cycle a little bit different is fixed rate borrowing was around 20% of total lending during the last cycle, whereas over the last 18 months, it's become as high as 50%,” Dr Oliver said.

“There's a bit of a lag between the rise in interest rates and when property prices started to fall.”

To illustrate this, Dr Diaswati Mardiasmo, Chief Economist at PRD, put together a graph comparing the cash rate to house price growth.

“Historically speaking, if we look at the graph, the first cash rate cut did not immediately result in property prices cooling down – in fact [prices] went up, as the potential of another cash rate increase was possible, and people wanted to be able to purchase their property at the new cash rate price before there were more cash rate hikes,” Dr Mardiasmo told Savings.com.au.

“Back in 2009 it took several cash rate hikes, in succession, over a period of time of roughly a year, before we saw a cooling down in price.

“There is always a lag between when cash rate hikes happen and the translation into property prices, and this is likely what will happen to our market, especially considering we are in a completely different situation than 2009.”

Dr Mardiasmo mentioned a few differences between now and the interest rate hikes in 2009. She said the current demand is mostly local, as the international demand for property has not yet reached pre-pandemic levels. There are also construction challenges and delays due to supply and worker shortages.

“The deep supply and demand imbalance right now may result in an even longer lag time between when the cash rate hike translates into property price,” she said.

Pictured: Diaswati Mardiasmo, Chief Economist at PRD

Dr Oliver said the signs of property price weakness are probably already showing and will become more evident earlier than it did last cycle due to increased fixed rate borrowing, which he attributes as a driving factor of the housing boom.

“The other thing is that debt levels are higher today than they were back then,” he said.

“People have been borrowing on much lower interest rates, which has enabled them to borrow more. And that that means the property market is probably more vulnerable than it was back then.”

Should borrowers brace for the worst?

With all of this in mind, what is going to happen this time around? Firstly, let’s look at existing borrowers who may have purchased within the past two years may be in for a shock.

“Some people would have borrowed at less than 2%, and if their fixed term is coming up for renewal soon, they may suddenly find that [they] can't refinance to 2%, [they] can’t rollover to 2%, [so they may] have to roll over to 4%,” Dr Oliver said.

“That's going to be a bit of a shock to some people. And it comes with the risk of people struggling in terms of their [mortgage] repayments.”

CommBank half-year results show $89 billion in fixed home loans are due to expire in 2023.

Dr Oliver said that the last cycle tells us that property prices go down when interest rates go up, but that the risks are that the falls could be greater this time around.

“Borrowers are not as attuned to higher rates as they were in the past,” he said.

Dr Oliver mentioned APRA tightening its serviceability buffer from 2.5% to 3% last October, which means that lenders assess borrowing capacity based on the home loan rate plus a 3% buffer if interest rates were to rise.

“If interest rates only rise 2%, you could argue that this would be within the serviceability buffer. And people may not really have a major problem,” he said.

“But it's still a source of uncertainty… you just don't know, it hasn't been tested yet.”

Dr Mardiasmo said those on variable rate mortgages are most likely to feel the impact of the cash rate hike, as many banks and lenders have already jumped the gun and increased their fixed and variable rates before the RBA moves.

“People are already dealing with a change in the mortgage lending space, and potentially in their mortgage home loan repayments,” Dr Mardiasmo said.

“As of December 2021, the family income required to meet mortgage repayments was at 37%; and most measures will say 30% or more means you are heading towards mortgage stress.”

For those hoping to jump into the property market in the near future, there’s some good news and bad news.

“The predominant impact [of the cash rate hike] is the reduced level of demand that will follow from higher interest rates, meaning people can borrow less,” Dr Oliver said.

“But this time around, there is more risk on the supply side as well.”

Dr Oliver mentioned the recent macroprudential tightening in 2017, which mainly affected investor lending but still saw property prices fall 10%.

“But [that situation] was not really comparable. I sort of think that, given the high risk this time around, we will see prices come down, but the risk is they will come down by more,” he said.

“We're forecasting a 10 to 15% drop in prices over the next two years or so.”

Housing affordability is far worse

We asked Dr Oliver whether housing affordability is worse now than it was the last time interest rates hiked, and he said it is “far worse” today.

“What was easier back then was saving the deposit to get into the property market, because the prices were a lot lower relative people's incomes,” he said.

“Yes, you had high upfront interest costs, but your wages tended to go up faster. And so the burden diminished quickly.”

He said that lower interest rates may have enabled people to take on huge debts, which is what made buying a property viable, but it now takes seven or eight years or longer to save up the deposit to squeeze into the market.

“You're lumbered with that debt for a lot longer... and it just takes so long to get into the property market,” Dr Oliver said.

“I would say that affordability is far worse today than it was back then.”

Dr Oliver said that if interest rates came down and house prices didn’t go up, affordability would have improved, but the reality is that that hasn’t happened. He also mentioned the lack of new housing supplied relative to population growth.

“Any affordability improvement from low interest rates has been totally offset by high house prices,” he said.

“The higher house prices have been sustained, because we haven't supplied enough housing.”

Ridiculous government policies

Dr Oliver called the housing affordability situation a mess, and said that the government doesn’t take it seriously because most voters own their own houses.

“They say nice things, but they don't really do anything about it. All they do is [provide incentives that] enable you to borrow with a 5% deposit, which is just ridiculous,” he said.

“That just means you end up with more debt than ever. It's a ridiculous policy.”

See Also: Should I hop on the First Home Loan Deposit Scheme?

Image by Lukas Blazek on Unsplash

Ready, Set, Buy!

Learn everything you need to know about buying property – from choosing the right property and home loan, to the purchasing process, tips to save money and more!

With bonus Q&A sheet and Crossword!

Harry O'Sullivan

Harry O'Sullivan

Denise Raward

Denise Raward

Brooke Cooper

Brooke Cooper