A survey not too long ago found 40% of Australian adults wished they’d been taught more about money as a child. I would be one of these former children. Although I consider myself to be quite financially literate now, things might have been quite different if I didn’t end up writing about finance for a living. Thinking back to my school days, I may have learned a lot of useful things but I’m fairly certain anything related to superannuation, tax returns and deductions, comparing banking products and how a mortgage works were not in the curriculum. And before I ended up doing what I do, I honestly didn’t even know how a credit card worked.

That royal commission we had into banking a thousand years ago now found “frightening” levels of illiteracy contributed to many of the issues raised in the final report, and even now, nearly 40% of Aussies lose sleep over money problems and more than 60% admit to regularly feeling ‘hot and stressed' about it.

This isn’t conducive to a healthy society, and the problem starts from an early age. Children should be taught such things in schools, but most of us aren’t. A quarter of Australians weren’t taught about money as children at all, so it’s no surprise that so many adults struggle with basic financial concepts. According to Raiz research, 75% of us believe schools aren’t doing enough to teach essential financial skills to the next generations, and I’m one of them.

Financial literacy leads to a healthier society, but many of us struggle with it

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “financial literacy is a core life skill for participating in modern society”, and this is especially true as we transition towards a cashless payments network. Financial literacy levels among older Australians are considered to be at “dangerous levels”: 9 in 10 Baby Boomers, for example, failed to get any answers correct on a simple three-question quiz.

But financial illiteracy is most prevalent among young adults. The OECD’s 2015 study found 20% of students aged 15 in Australia do not reach the baseline level of proficiency in financial literacy. Australia ranks 6th, behind the likes of China, Belgium, Canada and the Netherlands. While Australia is technically above the global average, levels of literacy around the world are quite low, and should be a lot higher.

Financial literacy is strongly correlated with mathematics and reading performance, as around 71% (vs 62% on average) of the financial literacy score reflects skills that can be measured in English and Maths. According to the OECD, “this suggests that students could be helped in using the skills widely taught in school to attain higher levels of financial literacy.”

Kids with harder upbringings struggle more with money

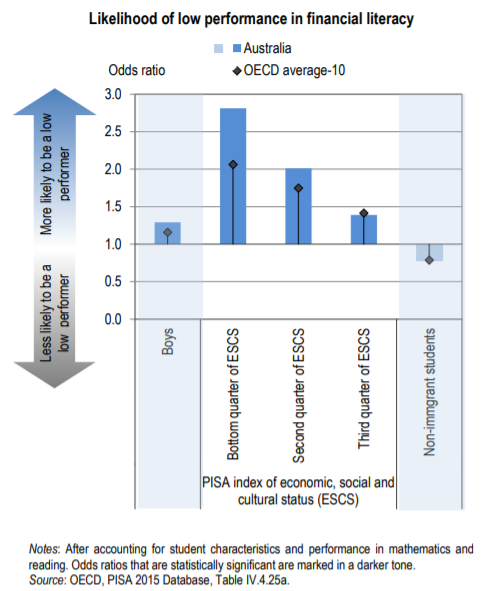

Although many Australian kids (15% of 15-year-olds) are top literacy performers compared to 12% on average, the OECD also noted that higher scores are highly-correlated with socio-economic wellbeing, more so than the OECD average. Students in higher socio-economic groups performed around 12% better than those in the lower socio-economic groups, and those who performed better were more likely to receive money as gifts from their parents and discuss money with their parents.

Given the correlation between low-income groups and low financial literacy, relying on parents to bear the brunt of teaching kids about money won’t work for struggling families, leading to even more Australians who don’t know the basics.

We’ve relied on ‘school banking’ for too long, but it doesn’t seem to work very well

Much of the share of teaching ‘financial literacy’ has for a long time been dominated by ‘school banking’ programs, which are courses run by banks in public schools. In 2019, the ABC reported nearly two-thirds of the nation’s schools participated in school banking programs, the majority of which was done by the Commonwealth Bank’s ‘Dollarmites’ program. These banks pay a commission to each school to run their courses in them - in 2019, Australian banks paid $2.1 million in fees to public schools.

While the intentions of these programs seem simple enough, there’s a lack of evidence to show that they work, and schemes such as Dollarmites attracted fierce criticism during and after the royal commission, with accusations they funnelled children into inappropriate financial products until adulthood.

In 2020, the Victorian Government announced it would ban such schemes in 2021.

Catherine Attard, Associate Professor in Mathematics Education at Western Sydney University said we’ve relied on these schemes for too long.

“Financial literacy is much more complex than simply building the habit of banking money on a regular basis,” Professor Attard told Savings.com.au.

Professor Attard has also previously said schools are not the place for such programs, and other alternatives need to be considered.

“If we consider the core business of schools to be learning, then our classrooms are not an appropriate place for the distractions of corporate marketing. There is definitely no time to be wasted on the logistics of organising school banking,” she wrote in The Conversation.

Some financial literacy is taught in school, but some say it isn’t enough

To clarify, Australian students are taught about money to varying degrees in our current state and national curriculums. While the Australian Curriculum doesn’t have an explicit financial literacy curriculum, such topics feature prominently within learning areas such as Mathematics and Humanities/Social Sciences courses, as well as economics and business subjects in later years.

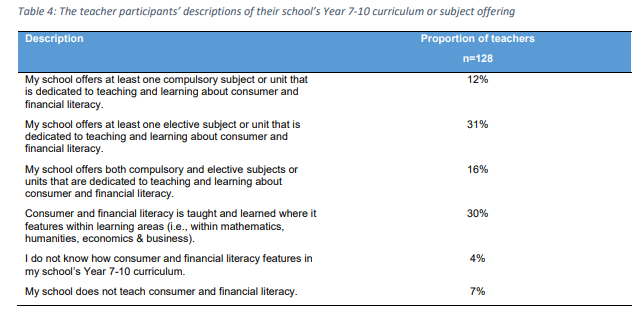

According to a study by Monash University, 30% of surveyed teachers said their schools taught consumer and financial literacy within certain learning areas, and 31% said their school offers at least one elective subject on it. Just 7% reported no financial literacy at all.

Source: Monash University

While the current curriculum gives students the chance to learn about solving problems with money, it’s mostly up to the different schools and the teachers to decide how the curriculum is implemented, and most teachers rely on free government resources for teaching finance, such as ASIC’s MoneySmart, or they rely on bringing in guest speakers to do it for them.

“While financial literacy is embedded into the curriculum, there is more work to be done inside and outside schools,” Professor Attard said.

“Schools need to make sure financial literacy is explicitly taught in conjunction with key subject areas. A way to ensure this happens is to have it made more explicit in the Australian Curriculum.”

So should financial literacy be its own subject at school?

A greater emphasis on financial literacy in schools isn’t a new idea. The OECD Guidelines on Financial Education in Schools recommend that member countries:

-

integrate financial education into the school curriculum

-

include financial education from the beginning of formal schooling

-

allow for flexible school-based curriculum implementation

-

encourage standalone and cross-curricular approaches

-

provide appropriate financial and in-kind resources

-

ensure suitable involvement of important key stakeholders

-

support the education system in the provision of teacher education.

Meanwhile, Australia’s chief tax agency the ATO believes important topics like tax and superannuation need to be covered more, with a majority of Australians with school-aged children agreeing.

“Since all Australians are required to pay tax and invest in super, it stands to reason that all school students should have the opportunity to learn about the taxation and superannuation systems, from the economic rationale underpinning their existence, to the practicalities associated with navigating them effectively, and how to access quality, trustworthy help when you need it,” a report commissioned by the ATO said.

One of the report’s authors, Dr Carly Sawatzki, Lecturer of Education at Deakin University, also believes it should be its own subject.

“Students stand to benefit from an explicit focus on economics and finance at school and dedicated subject offerings are a great way to achieve this,” Dr Sawatzki told Savings.com.au.

“Finance topics are often presented in ways that are dry and boring. Yet schools and teachers seem highly motivated to shake things up and recognise that students enjoy and benefit from lessons exploring economic and financial issues.

“Government-funded teacher professional learning together with the development of topical, innovative resources would be valued by schools and teachers.”

Professor Attard says financial literacy in schools can help society in many ways.

What would a finance course in school look like?

This question becomes tricky to answer. From this journalist’s non-expert point of view, it would make sense to cover topics such as taxation and superannuation, as specified by the ATO, while other crucial topics could be:

-

How bank accounts work (and how interest is earned) on savings accounts

-

How credit works, and the danger of relying on it

-

How a mortgage works

-

How to compare financial products and the importance of doing so (fees, interest rates, hidden traps etc.)

-

Strategies for earning incomes, and the cost of living

-

Basic economics, and the role governments play in personal finances

Of course, this is an overly simplistic view of how all this would work, and the reality is far more nuanced. According to Dr Sawatzki, students need to be taught about how their personal financial decisions take place against the backdrop of the economic climate, and to be sceptical and resilient in the face of an ever-changing financial system.

“Financial prospects often rely on government and organisational systems. The coronavirus recession has brought this into sharp focus. So, while it is important to teach students about taxation and superannuation as community assets, they must be able to negotiate important decisions like, ‘I'm eligible, but should I tap into my superannuation?’” she said.

See also: Many people withdrawing super early don't understand the long-term consequences.

“Financial and technological innovation is driving a shift in what and how we teach students about money at school.

“For example, research shows that young people distrust banks, are worried about personal debt, and consider credit cards to be risky and costly. However, they find buy now, pay later services like Afterpay very appealing.

“This necessitates teaching students to compare the fee structure associated with buy now pay later services with traditional credit cards.”

Read: Why buy now, pay later is so popular with young Australians.

Professor Attard says certain topics should be split into primary and secondary school learning.

“There are quite a few topics that could be covered in a secondary course – budgeting, lending (personal loans, credit cards, mortgages), tax, superannuation, and consumer literacy (understanding ‘best buys’ etc.),” she said.

“For primary students, simpler concepts such as budgeting, consumer literacy (looking at best buys relating to shopping, mobile phones, etc.) and simple borrowing concepts could be integrated into existing curricula.”

The key takeaway from these experts and various research papers on the subject is that the broad goal of teaching financial literacy should be to teach our nation’s kids on how they can make informed financial decisions, and not just on the basics of what financial products are or how money works.

“Financial literacy in schools will help society in many ways. On an individual basis, our young people will leave school being able to make sound financial decisions relating to their personal finances,” she said.

“Such decisions may have long term impacts on their life options.

“Similarly, a strong understanding of consumer and financial literacy can lead our young people to question unfair structures in our society, leading to improved, equitable systems.”

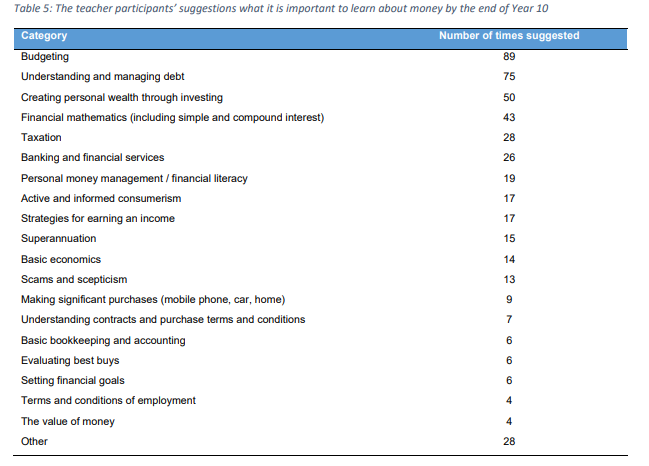

Here’s what our teachers think should be taught for financial literacy (128 teachers surveyed). Source: Monash University.

At what age would kids start learning about money in school?

Another tough question to answer is at what age should financial literacy be its own subject, and whether it should be taught with a ‘softer’ approach in younger years as a part of existing subjects.

Professor Attard believes that financial literacy should not be its own subject in primary school at least.

“There are many elements of financial literacy that can be integrated into our existing curriculum. We don’t want to be adding further work to an already crowded curriculum,” she said.

“I think the best way to address financial literacy is to make it more visible for teachers via the Australian Curriculum General Capabilities. If financial literacy was embedded into the General Capabilities more explicitly, teachers would then be more likely to address financial concepts in their everyday teaching.”

However, Professor Attard is more open to the idea of financial literacy being a standalone subject in secondary school.

“Financial literacy becomes more critical as students near the end of their formal education, and having a mandatory course (or even a short course) would be of benefit to young people who might already be earning an income, planning a car purchase and making other important financial decisions,” she said.

Dr Sawatzki also thinks financial learning in schools should scale:

-

“Early lessons involve children role-playing scenarios involving money through play”

-

“In primary school, students learn to calculate change and prepare simple financial plans.

-

“In secondary school, they learn more about the role of government in managing economic conditions and the range of money-related decisions adults face (earning an income, balancing the household budget, saving for the future, donating to worthwhile causes).”

Prior to school, parents should also endeavour to teach their kids about money, whether that’s by simply involving them in the purchasing process when going shopping, teaching them how to save their pocket money, or by helping them reach a certain goal for buying a toy. But given the earlier evidence presented by the OECD that kids in low socio-economic households perform worse in financial literacy, we cannot rely on just the parents.

“Parents do have an obligation to teach their children about money, but the problem with that is not all parents have good financial habits. We need to educate the whole community, not just school students,” Professor Attard said.

“We also need to ensure that the teachers in our schools have access to professional development so that they are able to confidently teach sound financial skills.”

Savings.com.au’s two cents

If one good thing has come out of the pandemic of 2020-21, it’s that it has made us more aware of our finances and what causes certain underlying issues. Given we’ve already semi-revolutionised other aspects of daily life, like working from home, why not also change up our school curriculum to make learning about money and banking products its own course in our nation’s schools, or at least by placing a greater emphasis on it in our current curriculum?

A greater understanding of money, financial products and the economy, taught from an early age, can lead to a more prosperous society with more engaged citizens in a number of ways, as higher levels of financial literacy are strongly correlated with:

-

Improved rates of savings and financial security

-

Lower levels of personal debt (such as credit card debt)

-

Increased levels of asset accumulation, and a greater net worth

-

A decreased tendency to rely on family for money and support

-

A healthier understanding of financial risk

It also leads to greater tendencies to save towards retirement and increases chances of regular employment. According to the RBA, such benefits “extend well beyond stronger household balance sheets to the promotion of a more resilient financial system and, ultimately, to the more efficient allocation of resources within the real economy”.

We’ve seen the consequences of poor financial literacy firsthand. Although the banking royal commission exposed the faults of executives, brokers, insurers, wealth managers and banks, it could be argued there would have been fewer scandals if customers had greater understood the risks and benefits of the products they were applying for, and if they were suitable for them. The RBA goes one step further, saying the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) happened in the United States because “it is quite clear that many of the users of US sub-prime mortgages – loans made to borrowers unable to qualify for a traditional mortgage – never fully understood the risks of borrowing this way.”

Financial literacy matters, and we can and should be doing much more to teach our kids how it all works, especially in the era of easy credit and online, cashless banking. Relying on banks to teach our kids, or even assuming individual parents have the skills to do so, isn’t sustainable.

Photo by NeONBRAND on Unsplash

Emma Duffy

Emma Duffy