Australia is slowly becoming spoilt for choice when it comes to electric vehicles (EVs). It used to be that Tesla was basically the only player in the game, but now other mainstream manufacturers are offering very compelling options. There are quite a few affordable models around $50,000 too, so you no longer need to sell a kidney just to go green.

However, at the end of the day, unless you’re running your home’s electricity entirely off sustainable power such as solar or using a 100% renewable energy plan, you’re probably still burning some coal to charge your EV. As an emerging green power source globally, this is where hydrogen cars could put your mind at ease.

What are hydrogen cars?

Hydrogen cars, or fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), use hydrogen to power vehicles along. If you’ve forgotten Grade 9 chemistry and the periodic table - we don’t blame you - then hydrogen is the lightest and most readily available element on Earth. As you might remember, water is H2O: two hydrogen atoms, and one oxygen atom. When you think about it, refined oil makes just as little sense to power a car, and yet here we are.

But enough of the chemistry lesson. How do they actually work?

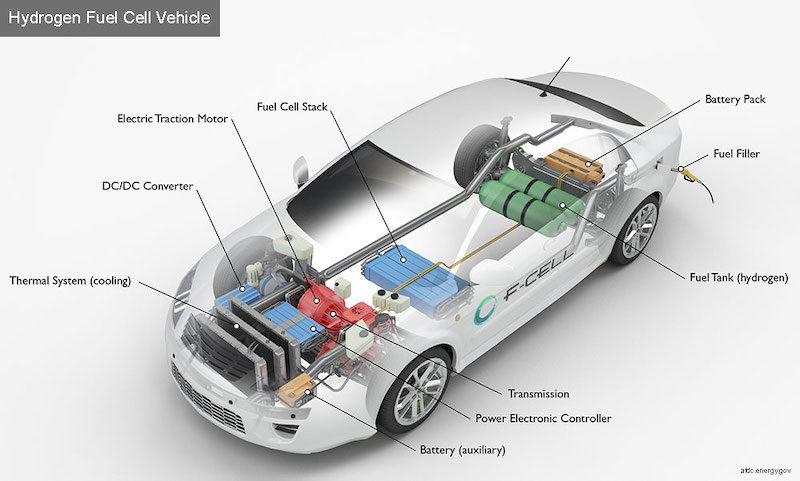

Source: US Energy Department

How do hydrogen cars work?

Hydrogen cars are somewhat of a blend between an electric vehicle (EV) and an internal combustion engine (ICE), which is just a regular petrol or diesel engine. Like EVs, Hydrogen cars have an electric motor, but unlike EVs, they do not use a lithium-ion battery that requires recharging. Instead, hydrogen cars use hydrogen gas to power the motor.

Powering the car along is done through the fuel cell, which produces electrochemical reactions between the fuel (hydrogen) and oxygen in the air. Like with ICE cars, hydrogen cars generally rely on such a ‘reaction’ or mini-explosion of sorts to power the car along.

Some of the benefits of FCEVs touted include faster refuelling times than EVs as well as better range. For example, the Toyota Mirai, according to Popular Mechanics, has the shortest range of any fuel-cell sedan currently on the market, yet still achieves 317 miles (510km) to a tank of hydrogen. This is better than many EVs, which feature ranges of around 400km or even less.

So, think of hydrogen gas as the fuel: there is still a consumable product that powers the car, but instead of polluting with petrol or diesel, the engine uses hydrogen, which is much cleaner. And the way water vapour is expended is quite funny as you can see in the video below.

Hydrogen fuel pumps in Australia

According to the ABC, the Queensland University of Technology hosts the state’s only hydrogen refuelling station. There is also a hydrogen fuelling station at Hyundai’s Sydney head office, and the CSIRO is building one in Melbourne. While there’s quite a distance between the three right now, the good news is that there are big plans for more, with stations set to be built over 2021 in both the ACT and Victoria.

If you’re intrigued by FCEVs, you might be wondering how to actually fill one up with hydrogen. It’s mostly the same as what we’re used to with petrol or diesel cars. When you’re running low, you pull into a station with hydrogen fuelling capabilities, lift the fuel flap and the nozzle, and refuel accordingly. While the process is called ‘recharging’ instead of ‘refuelling’, it’s essentially the same thing and can be just as quick, so you can still spend time at the servo finding the right choccy milk to buy!

This is in contrast to the EV refuelling/recharging process, which in Australia at present is generally a hodgepodge of charging stations scattered unreliably throughout the country. The Government has announced a few measures to tackle the ‘range anxiety’ issue, but there’s still a ways to go. Shopping centres also often have recharging stations, and you can leave your car on charge overnight in your garage (if you have one). However, if you’re on a road trip and near 0% charge, a regular charger - unless you have Tesla and can use a supercharger - can take more than an hour to charge to an acceptable level.

Hydrogen cars in Australia

Hydrogen cars globally, and especially in Australia, are nowhere near at the market saturation levels of EVs, which are already well below the global average here. When you think of EVs, brands like Tesla, Hyundai IONIQ and the Nissan Leaf have become pretty much household names, but you probably can’t name a hydrogen car model. That’s because there aren’t any mainstream, readily available examples in Australia… yet.

At the time of writing, Toyota recently unveiled a new hydrogen production plant in Melbourne’s west, and the Hyundai Nexo hydrogen SUV has been certified for sale in Australia, becoming the first vehicle to do so.

Twenty models have been delivered to service the ACT Government’s fleet, and further north in Queensland, Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk unveiled its FCEV plan in 2019, committing $19 million towards its hydrogen industry strategy until 2024.

In August 2021, Hyundai deployed five Hyundai NEXO vehicles into the Queensland Government fleet (pictured above).

The Hyundai NEXO has a range of 666km, with a refuelling time of three to five minutes, and is the first hydrogen-powered car in Australia.

Hydrogen car models

These models are currently either in production or are being prototyped:

-

Toyota Mirai

-

Hyundai NEXO

-

Mercedes-Benz GLC F-Cell

As it stands, there are no mainstream hydrogen car offerings available yet to the Australian public. The Toyota Mirai is currently only available in some US markets, though on its website Toyota does say it is coming to Australia.

Savings.com.au’s two cents

It’s an exciting time to be an alternative-fuel car nerd. No longer are electric vehicles basically the only option when it comes to green motoring. Hydrogen vehicles, while in their infancy, are surely only a few short years away from being viable.

One big benefit hydrogen cars have over their electric counterparts is they are fuelled just like regular ICE vehicles. You stop in at a service station, fill up the tank and off you go. This compares favourably to EVs which usually need to be left on charge overnight, lest the motorist be prepared to wait a while at a charging station.

Still, EVs have far superior market saturation despite their relatively low numbers here and are likely to be the more popular green vehicle choice for some years to come.

Article first published 9 April 2021, last updated 23 August 2021.

Photo by Toshihiro Gamo on Flickr

Ready, Set, Buy!

Learn everything you need to know about buying property – from choosing the right property and home loan, to the purchasing process, tips to save money and more!

With bonus Q&A sheet and Crossword!

.jpg)

Harry O'Sullivan

Harry O'Sullivan

Harrison Astbury

Harrison Astbury